“The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing that stands in the way.”—William Blake

“How did you even know about this tree?” my husband inquired. We were trudging through the woods in rain gear and rubber boots in pursuit of one of the few remaining old-growth Western Red Cedars—one of the biggest I was told.

“Huh. I don’t actually remember,” I responded. I genuinely could not recall who had told me about this tree. But I know what inspired me to seek.

A few years ago, I encountered the Coast Salish story of Grandmother Cedar. The story tells of a lone cedar tree who is given a grandson cedar by the Great Spirit to cure her loneliness. To help him survive, she lovingly moves her branches and scares away critters who want to eat him. She protects him from the wind, and shades him from the sizzling sun. Many winters pass and he grows tall. Grandmother Cedar becomes old and tired. Grandson Cedar says, “Grandmother, you protected me from the wind, sun, and critters. Now that you are old, I will do the same for you.” And so, Grandson Cedar cares for his beloved Grandmother Cedar.

I grew up with a row of Western Red Cedar trees in the backyard. We kids would climb their branches and play under the canopy in the spongy red bark dust. Back then, they were just tall green things. After I found the tender Grandmother Cedar story, they became more than just tall green things. They became precious. The story showed me the gentle side of nature - allowing me more access to peace. To the story, and the tellers of the story, I offer my gratitude, reverence, and softened heart.

In Latin, Western Red Cedar is called Thuja Plicata. Thuja, meaning “fragrant” and plicata meaning “folded into plates.” This refers to the unique foliage - froths of tiny leaves resembling flattened braids. Western Red Cedars are so arresting, aromatic, and useful, they are referred to as Tree of Life, or Long-Life Givers by some Coast Salish tribes. Indeed, standing inside a cedar grove, under the steepled canopy, inhaling the oxygen the trees exhale, and enveloped in the lemony-pine aroma, really is a religious experience.

To Coast Salish people, the fragrant fronds hold spiritual and healing significance and are used medicinally in teas, decoctions, smudges, and salves. This Tree of Life provided all for these tribes, from birth to death. Besides cradles and coffins, the Western Red Cedar was used to make canoes, housing planks and posts, bentwood boxes, tools, baskets, clothing, hats, dishes, harpoon and arrow shafts, barbecue sticks, totem and mortuary poles, herring rakes, fish spreaders and hangers, spears, spirit whistles, dip net hooks, fish clubs, masks, rattles, benches, drum logs, combs, berry drying racks, paddles, and even menstrual pads and diapers.

Harvesting the bark was a task that the women passed to one another through the generations. Young girls would go with their mothers and grandmothers to gather from Grandmother Cedar. When they found just the right cedar, prayers were first offered. Then, to harvest the bark, they would make a horizontal cut in the tree and pry upwards to loosen it. The women were careful not to kill the tree. After all, she is a Grandma.

The bark would be hung, dried, and laboriously shredded using deer bone, until it was ready to be woven into things needed to sustain life such as blankets. This maternal tree elder who had protected Grandson Cedar from the elements also protected the people from the elements by wrapping them in her loving bark.

Prior to European contact, few cedar trees were actually felled by the Native Americans stewarding the water-soaked lands where these trees live. They used downed logs, or boards split from standing trees. They would use wedges from antlers or yew wood pounding them into the living tree to split off cedar boards so that they could make half logs for canoes. This did not kill the hardy cedar, after all it is a Tree of Life. Rather, they used only what they needed since they venerated this tree. To them, the cedar trees were not seen through the lens of profitable board feet and totaled up like a purchase order, but instead through the lens of relationship, which naturally resulted in sustainable harvesting that was sure to make their days long in the land. In this tree is Grandmother, Grandson, and then Grandfather. To cut down the cathedrals of Cedar groves would be akin to bulldozing cathedrals like the Sagrada Familia in Spain. Grandmother Cedar is sacred family.

Recently, I visited a friend who lives on a large expanse of land. When we visited, he kindly gave us a tour of the land, which includes a historic home, a cedar wood barn, meadows, and forest. As I meandered through the forest, I was struck by how strange it felt. Instead of a path flanked by salmon berry canes, sword ferns, and Oregon grape, there was almost exclusively a dusty bed of sorrel. When I looked up from the path, I noticed the trees were all alike. Starkly spaced apart equally and the same size. This was no natural forest. This was a replant after a clear cut. What I was seeing were Douglas fir trees, about 30-years old. The favored trees to plant since they grow straight and can survive in a single species forest.

Someone had blazed trails through the nascent forest and made signs marking the trails. One sign said, “Row of Elders,” with an arrow pointing leftwards. We turned left at the homemade sign and walked by five voluminous cedar stumps. Each one was the size of a Buick! These were the elders. On one stump, evidence of saw attempts remained. The tree’s girth had been so thick, that the loggers had to move upwards to chew through a narrower portion of the tree in order to fell what must have been a monumental matriarch. I wondered how many individual growth rings there were before the continuation of life was amputated into a lowly stub. In the Row of Elders, there were no cloud-piercing treetops, chunky J-shaped branches, or droopy feathery fronds. No birds made their nest there. All that remained were the dead cinnamon-red stumps. “More like a cemetery of elders,” I cynically thought to myself.

That evening, I went to bed with a heaviness. In that silent forest bereft or birdsong and even insects, the Row of Elders showed me something precious that was taken long before my existence was even a glimmer. Growing up in the Pacific Northwest, I had seen plenty of cedar trees, but all the trees I had seen were less than a quarter the diameter of the practically prehistoric stumps I had seen that day. I realized that my heaviness stemmed from a sense of loss. I had never, in my middle-aged life, seen an elder cedar in the wild, despite growing up right in the middle of their native lands. Not even one! The past had plundered my future.

“One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives with the wounds of the word.” –Aldo Leopold A Sand County Almanac

Cedars commonly live to 1,000 years old, even up to 1,500 years. No wonder that Coast Salish story depicted them as Grandmother. No wonder they have been referred to as elders. But the past had killed our tree elders. They lopped off the life of the wondrous gargantuan cedar groves and left us a monoculture of little Douglas firs. Of course, this was nothing new. Acres of forests had been cleared to make way for civilization. Even Portland Oregon, was once referred to as Stumptown because the town had so many stumps from where trees once stood. Today, both the trees and stumps are gone - paved over with concrete and asphalt - a famous coffee company bears the name of the wounds inflicted upon the land.

After a while of trekking off-trail through the soggy forest, my husband exclaimed: “That tree is huge!” pointing across a ravine to an imposing Western Red cedar. We slid down the crevice, leapt across a small stream, and clawed our way up the other side towards the tree. Was this the cedar I had been told about? This cedar had a hollow inside, reaching up about 100 feet, and surrounding a large, buttressed base was the familiar rusty-colored bark dust. I sat inside in the in wonderment sheltered from the rain. I touched the fibrous bark and offered my gratitude for her continued presence. I opened a jar of gifts I had brought: Pacific sockeye salmon skins and nootka rose hips to ferment into the ground and give nutrients.

We laid them at the base and offered prayers of praise and thanks. After a while, my husband said “There is another big cedar over there!” I looked to where he pointed. There rising towards the heavens was a plump tree with that distinctive rutted red bark. I took another look at this hallowed hollow cedar, said my farewells, and wandered over to the next tree.

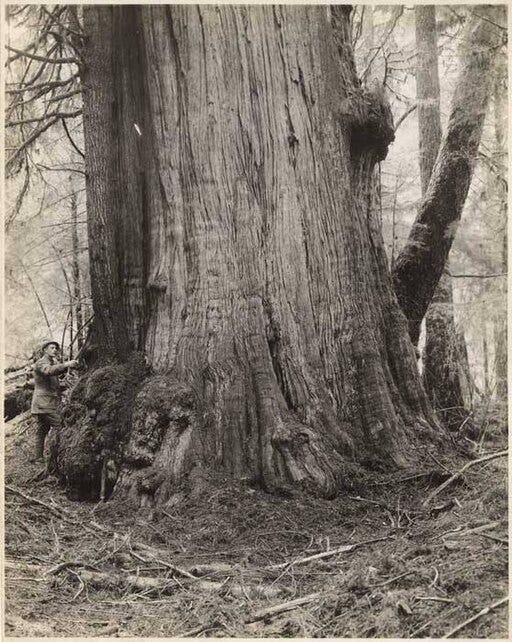

This cedar was even bigger! It had junior hemlock trees climbing up its thick trunk. Growing up higher, at the root of the arching branches, was salal. This generous tree supported the life around it. We stood at this second tree admiring the huge, fluted base and comparing it to the width of a minivan. I wondered who else had stood near her over the centuries. I imagined barefoot Native women, clothed in cedar, harvesting bark in supplication on that very same patch of forest I stood on. I felt gratitude for the Native American women who had honored their traditional ways, on these giving and forgiving lands. They had preserved this tree for the unborn future–which long ago was me. I couldn’t help but give into a sense of peace and thanksgiving.

“A tree retains a deep serenity. It establishes in the earth not only its root system but also those roots of its beauty and its unknown consciousness. Sometimes one may sense a glisten of that consciousness, and with such perspective, feel that man is not necessarily the highest form of life.” — Cedric Wright (violinist, photographer and mentor to Ansel Adams)

Knowing that this tree had remained in that patch of forest for centuries, serving such a different world that the one I inherited, begat an awareness of a mystery beyond the ways and thoughts of man. I stood there in enchantment until my husband alerted me to yet another massive cedar tree!

We made our way over to the next discovery. She was the biggest. This was the Grandmother of the Grove and of the forest. She must have had a waist of at least 50 feet! With her citrus scented boughs encircling her base, her celestial apex climbed heaven words and had even split in two! She must have been at least 800 years old. I couldn’t believe it. For the very first time, despite growing up in the Pacific Northwest, I was in the presence of ancient wild cedar trees. The elders did exist!

And then my astonishment turned to quite somber. Surrounding this great sacred Grandmother Cedar stood the profane - the common cinnamon-red cedar stumps that freckle our forests. A glaring reminder that the past robbed us. What remains are the scraps.

Why had she not been cut down like the others? She had been right in the middle of the logging operation - very much noticed. Maybe she was simply too big to get out of the forest. Reverently, I reached out and touched her damp purplish bark. Standing under her canopy, a sadness came upon me. Despite her grandchildren being commodified and harvested, she had an unshakable will to endure. She remained there for hundreds of years selflessly serving life.

For centuries, the remaining cedars had patiently stood in a ruined place, enriching it, renewing it. That sessile grove had cleaned the air—indeed created the air! It held the water in the earth, stopped soil erosion, provided homes and food for critters, and grew deep wide connecting roots, all while creating serenity and splendor. They made that little patch of foggy forest, so close to civilization, beautiful, healed, and alive. Why had they not succumbed to the logger’s blade?

I tell myself a made-up story about a very old logger who found the sacred through the profane. Employed by a multi-million-dollar timber company, he had made a modest living clear cutting the forests for decades. He could remember when seeing groves and groves of towering cedars was a common sight. Then he has a moment where he realizes that if he continues to chop down these elders, then his grandchildren would never know such wondrous presence ever existed. And so, he converts from a logger into a woodsman.

As defined by Jason Rutledge in the film Somehow Hopeful, “A logger is someone who converts the forest to the commodity of a log for a fee. A woodsman is someone who goes into the woods and addresses their needs in such a way that it guarantees that they can come back again." And so, this imaginary person has a heart change and begins to serve his unborn great-great-grandchildren whom he’ll never meet - even going so far as to falsify records saying all the trees had been harvested.

Or maybe an absent-minded someone merely forgot to go back and fell these financially valuable trees.

Under the majestic matriarch’s emerald crown and sweeping robes of lacy fronds, I knew that in seeking, I was sure to find miracles. Even among the stumpy profane stands the sacred - gifts of grace and hope for the unborn future.

In that scrap of Eden are the wounds and wonders - the senescent survivors and crumbling stumps. In their wisdom, they show the paths humans can take. Standing on the ancient red bark dust that day, absorbing the sacred and desecrated, I sensed the divine in nature, that the indigenous of this region already understood so intuitively, and a responsibility to cherish the remains of Creation.

"They’ve lost it. Lost it

and their children

will never even wish for it–

and I am afraid…

because the sun keeps rising

and these days

nobody sings.” –Aaron KramerIn this wounded world, may we be attentive to wonder. In praise, may we be moved by the overwhelming goodness that’s been silently there all along. As the trees grow taller and older, may we live in service to today’s young children, as they grow taller and older. May we be compelled to preserve wonder, for they will inherit the outcome of our decisions. Amen.

Thank you, friend, for missing, seeking , finding, and telling the beauty that is yours by birthright. I'm even more inspired to admire Templeton's grandmother oaks

I found this incredibly touching, healing, moving, and inspiring. Thank you for writing so tenderly about the beauty in this world Alissa.