Reducing Genesis to Words

From Living Oral Tradition to Static Words on a Page – Part One on Ancient Literacy

If I’m honest, I’ve never really enjoyed reading the Bible. I’ve much preferred to listen to a sermon or discuss the sacred scriptures in a community. I’ve always thought this is because I am an auditory learner, but maybe it’s because the Bible is designed not around the written word but oral tradition.

The Bible, specifically the book of Genesis, is based on oral tradition that, over time, was reduced to words on papyrus scrolls. In Genesis, we read that in the beginning was The Word. Not the scroll, not the stylus, not the parchment, not the codex, nor the book. In the very beginning, those items were not even in existence. It was just The Word.

The sagas in Genesis circulated orally for 2,300 years before they were ever written. The Bible did not begin as written language because written language did not yet exist. It hadn’t been invented. And so, to know history, the ancients relied on spoken relationships (oral tradition) versus abstractions (written language).

The extraordinary legends held in the pages of Genesis, such as the Creation story, the Great Flood, Noah’s Ark, the Tower of Babel, and Joseph and the Coat of Many Colors, were once held not in book libraries but exclusively in human libraries told by the ancient Israelites around campfires in the lands we now call “The Holy Lands.” Back then, The Word breathed with life – exhaling out of expressive mouths, riding on the timbre of human voices, reverberating across the Judean landscape and into the attentive ears of their listeners. The only way to access these tales was through a fellow person, not solitary reading. Learning this history required familial relationship, conversation, and the presence of others. And so the legends were told and retold in abiding human voices. Each retelling these preliterate people presented was its own variation with fluctuating stress patterns, changing loudness, hilarious exaggerations, and differing gestures. The listeners held these stories in their minds and hearts and orally passed them on through their breath to the next generations, each adding their own particular touches as time moved through them.

Imagine young Israelite children wandering in the desert with Moses. Picture them seated at the feet of an elder, gazing with rapt attention as Uncle Morty tells the story of a magnificent flood that was so gargantuan it covered the entire world! When he reaches the part where Noah releases a raven, he gesticulates wildly, flapping his arms like wings, protruding his neck forwards and backwards, leaping around, and mimicking the raven by croaking and grunting in changing pitches, causing his young audience to topple into giggles. To further engage and delight, he ups the vaudeville act using overdone animated facial expressions, extravagant words, and flamboyant gestures. The best part is when he flutters his eyelashes and croons and swoons as he depicts a dove soaring towards Noah pinching an olive branch in her beak. The wide-eyed children inhale in wonder with their mouths dropped open. By the time the story reaches its crescendo, Uncle Morty triumphantly declares that Noah was 950 years old when he died! The audience gasps in speechless astonishment.

But did Noah really live to be 950 years old? Or, was the story of the Great Flood told and retold with increasingly embellished details in order to entertain the listeners on those long, dark nights in the wilderness? Maybe, in this epoch, the world was so pristine and pure that lifespans stretched beyond what we modern people consider possible. Perhaps a diet of wild meat, along with roots and fruits grown in potent mineral-rich soil (before the invention of chemical agriculture), extended life to incredible lengths. I don’t know. Nevertheless, Genesis – the book based on 2,300 years of oral tradition – seems to feature numerous people who enjoyed unfathomable longevity. Once written language was used to preserve history, Biblical lifespans became more realistic. Moses himself lived to 120 years (see Deuteronomy 34:7). David is thought to have lived to about 70, as the Bible states: “David was thirty years old when he began to reign, and he reigned forty years” (2 Samuel 5:4). Eli was 98 years old when he died (see 1 Samuel 14:15).

I am told that in Chinese literature, exaggeration is a common literary tool to enhance the story. For example, instead of saying, “The man had a long, gray beard,” an author may write, “The man had a gray beard 3,000 feet long.” Recently, a friend was telling me how she has perfected her potato leek soup recipe. She said the trick is to use only Russet potatoes, homemade broth, and “about 5,000 leeks!” She claimed that her potato leek soup is simply the best there is. Point taken – if I want tasty potato leek soup, I’ll go heavy on the leeks. Had she written the recipe, she might have said, “add five leeks.” Much less interesting but much more realistic.

You want to tell me a story about a man called Methuselah who lived for 969 years? You’ve got my attention! Exaggeration makes language richer and more interesting. That’s the enlivening beauty of orally told stories.

To know my own past, I have relied on oral tradition. Most of my family lore is not recorded; it’s only passed on through the spoken word. The jokes my grandpa used to tell me are not written down; they reside within me and my memories. If the younger generation is to ever know these stories, their only access to this ancestral knowledge is through me.

One of my grandfathers died long before I was born. When I asked my aunt about him, I got to know him through her experiences: “He was such a kind man!” My uncle told me his memories of my grandfather: “I remember he would make me these little pocket watches out of milk lids. Back then, milk lids weren’t plastic, they were made of paper.” My dad told me that my grandfather was hospitalized for six months from a lung injury and that nobody could visit due to the tremendous difficulty of reaching the hospital from the deep woods where the family lived. I’m left wondering how that experience might have impacted his easy-going character.

None of these stories have been reduced to the written word (until now). But even as I write them, I cut out details so I can keep my reader engaged. I also cannot accurately depict the spirit of the stories told through the pulsating, living bodies of my relatives. There’s the twinkle in my aunt’s eye, the gentle posture my uncle takes on, and the nostalgic tone my dad uses. Reducing the orally told stories to written words forgoes the sparkle with which they were told. To access and hear these stories requires relationships and kitchen-table conversation. This is much more satisfying than reading silent inert words on dry, dead pages.

The entire Bible, especially the Old Testament, was written in a world where mass literacy did not yet exist. Most people accessed the Ancient Scriptures only through the Oral Tradition. In Genesis, the word was literally living. The later books of the Bible were intended to be read aloud in a public square. Even the written words of the Bible are uniquely for an oral purpose.

So, how did Genesis get reduced from the living Oral Tradition to stagnate words on a page? I don’t fully know. To really know the answer to that question probably requires attaining a PhD. Regardless, here’s what I have learned so far.

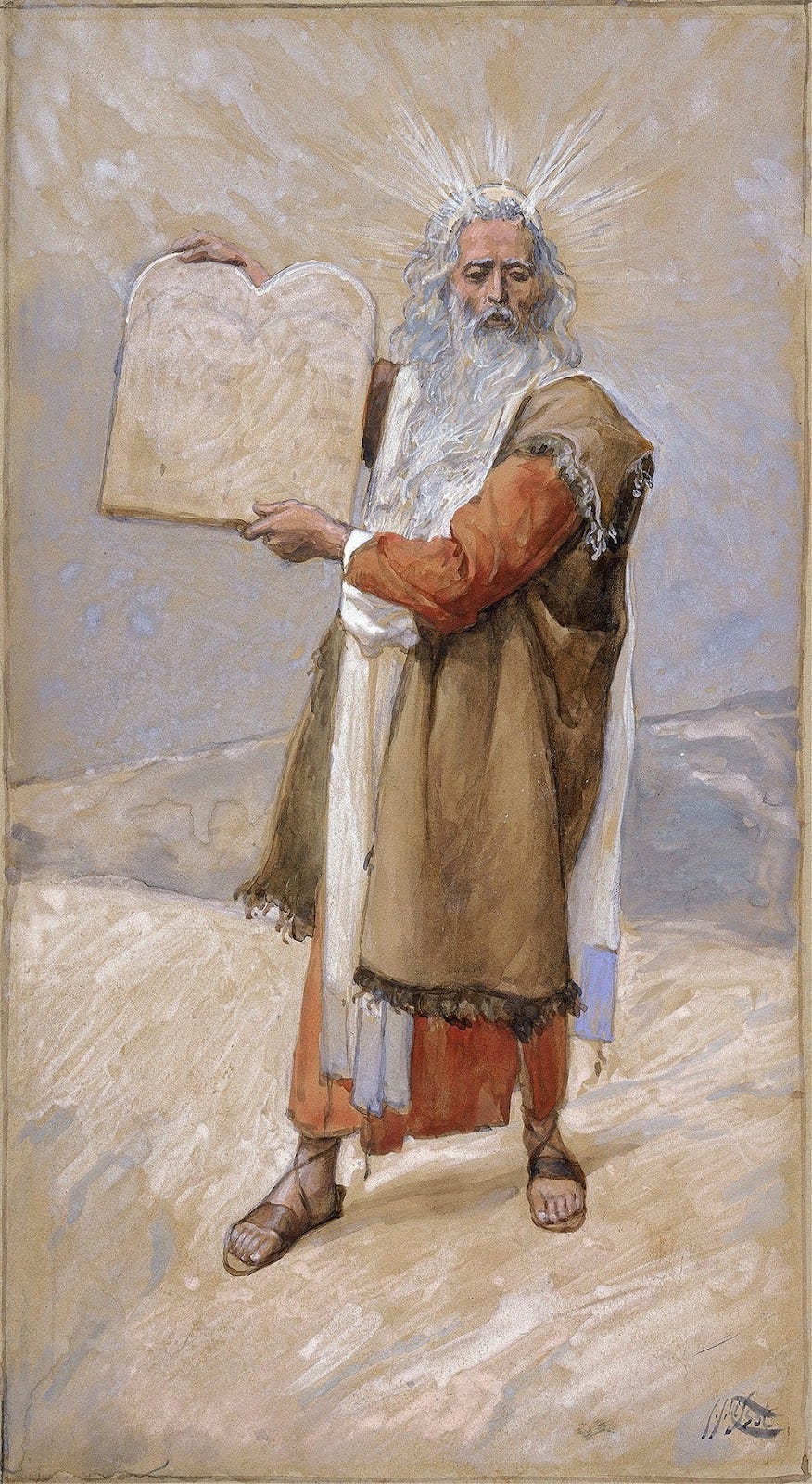

Moses is thought to have written down the first five books of the Bible. Perhaps he was the first literate Hebrew with the ability to write.

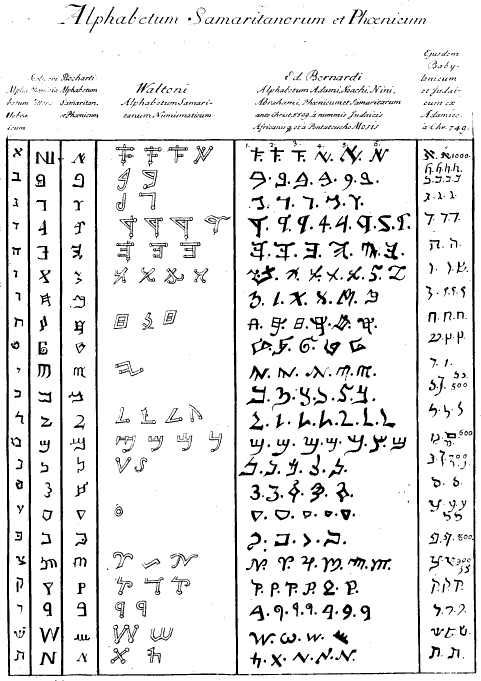

In the Fertile Crescent region, written language began as Egyptian hieroglyphs. In a preliterate world, hieroglyphs preserved history by using pictures. Most people did not learn to read or write unless they were elite in Egyptian society. This makes sense since Moses was raised not as a Hebrew slave but as an Egyptian prince. Acts 7:22 says, “Moses was learned in all the wisdom of the Egyptians, and was mighty in words and in deeds.” Given his upbringing, scholars surmise he must have learned Egyptian hieroglyphs. Eventually, this system became obsolete after the Phoenicians (previously known as the Canaanites) invented the phonetic alphabet, which is based on sounds and can express more nuanced ideas. The shapes of the phonetic sound symbols were derived from the general shape of previous hieroglyphic pictures that began with the sound. For example, the original shape (cuneiform) for the letter D resembled a doorway or “dalet” (the word for door), which became the Greek letter “delta,” and eventually our letter D.

Before paper was readily available, people used rocks, bark, and clay tablets as writing vessels. I can imagine Moses coming down from the mountain holding some clay tablets, except those clay tablets didn’t have something inane written on them (like a potato leek soup recipe). These clay tablets held the Ten Holy Commandments written by the finger of God, telling the Israelite people how they should live so “that their days may be long in the land God gives to them” (Exodus 20:12). I’ve wondered what writing symbols were on those clay tablets. What languages did Moses read, and which ones did he speak? Did he only know hieroglyphs? Did he know the phonetic alphabet and then apply that to the Hebrew language? It’s all a mystery. As far as I can tell, nobody really knows.

Besides clay tablets, rocks, and bark, the papyrus plant could eventually also be used to preserve the written word. Papyrus (sometimes called bulrush) came from the rolling streams of the Nile. As a baby, Moses floated upon this river in a basket, surrounded by the plant he would one day use to write the Israelite history upon. Fatefully, an Egyptian princess and her maidens approached the river to bathe. The princess saw the floating baby, took compassion on him, and raised him as a prince, naming him Moses, which simply means “son” in Egyptian.

The papyrus plant is a reed that grows up to five meters tall with a stalk about the thickness of a human wrist. To make paper from this plant, the stalk was cut into sections, the husk removed, and the pith peeled into thin strips. The strips were laid side by side in rows, then another layer of strips was placed over them in columns. The two layers were then pressed together so that the fibers could release a juice that fused the layers together. The pressed layers were dried and then meticulously smoothed with pumice and polished with shells. These sheets would be pasted together into long strips and eventually rolled into scrolls. These papyrus sheets were then shipped to the Lebanese port town of Byblos (a town where papyrus was traded) and distributed across the ancient world. Thus, the origin of the word Bible, or “The Papyrus Book.”

To make pens, papyrus reeds were simply split. The ancients could create ink from many commonly available natural materials: soot mixed with gum and water or wine mixed with resin. Pulverized oak galls (abnormal plant growths produced by wasps) boiled with water comprised the ink favored by Da Vinci. Today, some artists even employ used coffee grounds as ink!

In ancient times, every copy of a book was arduously produced by hand, not by a mechanical printing press. Unlike oral tradition, the written word was time-consuming. The authors had to be economical with words. I suspect that including all the orally circulated stories in the 2,300 years of Genesis would create a book 23,000 pages long. I’m sure many stories and details were omitted for the sake of efficiency. What we are left with all these millennia later is probably not definitive.

One day, I was listening to a Native American woman from a small, federally unrecognized tribe talk about her ancestry. She emphasized that most of her tribal legends have been lost since the tribe was decimated by plagues. She shared her tribe’s Creation legend. As she retold the story about how a bird had laid eggs upon a mountain, and the eggs rolled down the mountain, hatching people, I realized I knew the story. The story is memorialized in writing on a placard under a tribal monument on the east side of town. I wondered if the reason she knew that story was because it is written down.

Regarding my own history, I have a cousin who undertook the monumental task of reducing our family history to words. She wrote the story of our family in a book of about 200 pages. There are pictures of the ancestral village in Finnmark, images of genealogical records, along with numerous family photos and stories to accompany them. My great aunts and uncles (most of them now deceased) tell how they met their spouses, what towns they lived in, and why they moved around. There is a picture of my great aunt holding an octopus with her fellow cannery co-workers. One aunt wrote that her husband was a stowaway on a ship that came over from the Philippines. I never knew! There is a tale of how my cousins had hatched a plan to meet at the house on a specific date and time to take a family photo. One cousin decided she would get there by moped. Another lived across town and chose to walk over. Another was hitchhiking across the country to protest the fossil fuel industry. Would everyone get to the meeting place in time to take the family photo? Whew! Just in the knick of time, they all converged on the family home, and that moment was captured, snapped in a photo. Eventually, it was printed on the page of a book, and because of those written words, I got to know my relatives. Had these stories not been recorded, I think they would have been lost. I owe much gratitude to my cousin for helping me better know my ancestral past and, therefore, know myself.

Knowing that the Bible is built upon the oral tradition – written in preliterate times to preliterate peoples when orthography was still in its infancy – changes how I view the sacred ancient texts. The first alphabet didn’t even have vowels. The Hebrew word for God, “Yahweh,” was written as YHWH. Anyone who could read was expected to fill in the invisible vowel sounds.

When compared to our modern advanced written language, the prose of ancient writing was undeveloped with grammatical oversight, syntactical gaps, and semantic concepts that don’t have a suitable equivalent in English. This is one reason why the Bible is so confusingly worded. Not only is it written by many different authors, but it is based on oral tradition and a primitive orthography. What we read in Genesis is an unedited stream of thoughts. No wonder in one part of Genesis, it says plants came before animals, and then it goes on and flips the order! Oral language is like that. It's not as consistent as our advanced written language.

Orthodox Christian scholar, David Bentley Hart talks rather bluntly of his experience translating the New Testament:

“Where an author has written bad Greek [...] I have written bad English.”

This all explains why I have a hard time reading the Bible, and I much prefer to hear the Word. But still, I give my gratitude to the many authors of the written Testaments. They preserved the spiritual revelation given to Israel, which is to love, serve, and seek to understand God. The ancient Hebrew people attributed history held in these Hallowed Scriptures not to themselves but uniquely to “the mighty acts of the Lord.” The stories teach us to know God as a God of justice and love who asks men to reflect His divine nature by being people of justice and love too.

It’s an astonishing feat that written language evolved, that the innovative ancients figured out a way to use natural materials to make writing tools and vessels, and that millennia later, the Holy Bible still holds, deeply influencing society. The written words of Leviticus (19:18) give the profound command, “Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself,” which was echoed 1,400 years later by Jesus, and 2,000 years after Christ those immortal words have become the Golden Rule that is still taught in classrooms to this day.

In the preserved written words carried on the leaves of the Holy Bible are ancient genealogies, epic legends, songs, folklore, statistics, orations, jubilant hymns, lyrical poems, novels, and even boat-building instructions. The books of the Bible are written in many moods and styles, with the cadence and rhythm changing to reflect the hundreds of inspired authors transmuting the oral word into written words. Through these luminous written words shine the ever-guiding bright light of The Revelation of God. Thousands of years later, the written Bible has influenced visionary change. Who knew that this ancient text would inspire the minister Martin Luther King Jr. to lead his people to freedom? Or that the wisdom found in those pages would give rise to Alcoholics Anonymous – a life-changing program saving many from the destruction of addiction? This is the splendor of the written words shimmering off the pages and fluttering into the hearts of its followers 5,000 years on, calling believers to live in such a way that the fruits of the Spirit – “love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, and self-control” – become not only their character, but their destiny.

Divine Nature is intended to heal, inspire, and cultivate hope—thus, it is given freely.

Essays are published about every six weeks, or less. Please subscribe knowing your inbox will not be inundated.

Thoroughly researched and insightful study of the power and limitations of writing down stories. You clearly brought your speech therapy and linguistics skills to bear too! And I loved learning more about the Johnson clan. :) And I loved how you described so well how storytellers held their audiences' attention.

Love this and love the selection of photos/paintings chosen. Excited for more.